And just like that, the summer solstice is upon us, or will be on Thursday, June 20. Where did the year go, the eternal lament of most adults, those of us for whom the years seem to slip by in an ever-speeding montage, even in times when days themselves are interminible. I wish, we used to say as kids, I wish it was Christmas, I wish it was time for summer vacation, I wish it was my birthday, I wish it was the weekend. And our teachers or other adults would say to us, You’ll wish your life away. They were right, but sometimes you want to, maybe not your whole life, but I could do without the past year, and the year before that, for that matter. A few months ago I found a journal I’d kept in 2022 and 2023 and I soaked it with a water hose so that all the ink ran and the pages stuck together and then I tore it to bits and threw the soggy smeared remants away because I cannot think of anything I ever want to go back to less than my thoughts and observations during that time. And I will be nothing but glad when all of the grim anniversaries of the past year are more than a year behind me.

If you’ve been reading my letters here from the start, you’ll know that I’d chosen last summer solstice as my original start date for launching this project, but in the weeks before that, things had fallen apart in all kinds of ways.

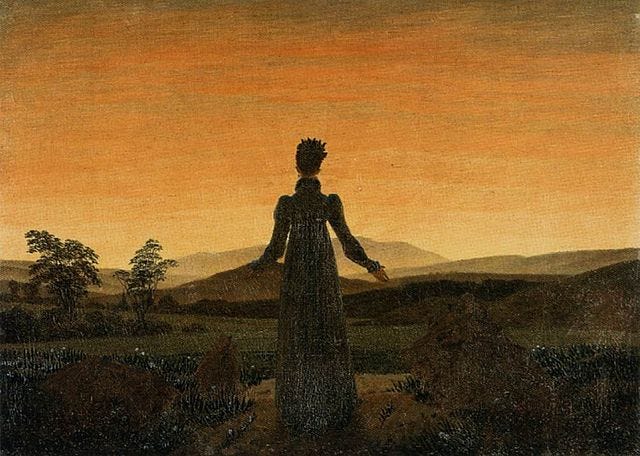

As for the solstice itself—if the winter solstice can never come fast enough, in normal years (the ones when I don’t want to just hurry everything along), the summer solstice always feels too soon, like I’ve barely begun to remember and bask in the glory of the light and now it’s going away. Growing up the southeastern US as I did, I used to take the light and the heat for granted until my mid-twenties when I moved to Portland, Oregon, a place where the encroaching winter really did mean a plunge into months that felt like years of darkness. Then I kept on landing in places where this was the case, and it’s like on some elemental level I’ve never really recovered, like there is some great expanse of cold dull grey frozen inside me that can’t seem to get warm again.

So the coming solstice makes me think of all the fear and despair I felt this time last year and the looming one-year anniversary that I would like to fast forward past. You can’t though, can you? You have to live through every single damn excrutiating second of your life, and I’m sure if I had five minutes left to live even those seconds might seem like glorious ones but from where I’m standing now the forgetting mechanism offered in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind seems tempting even though if we could wipe out all the painful things at will I think we would all become monsters.

It’s funny, though, the moments that stamp themselves on your memory. For some reason, I’ve been thinking a lot about something that happened when I took my mom for her first chemotherapy session.

We were apprehensive and hopeful about this appointment: Would her hair fall out? Would she vomit? Would she be able to eat? Would she shrink away to an even smaller and more fragile version of herself? Would it help? We’d been through all this with my brother four years earlier, me mostly though not entirely from a distance, and the answers in that case were yes, yes, no, yes, and no, so the apprehension was winning. She was super stressed, understandably, and angry at me as a result, so I was rattled, although I’m not sure her succumbing to the terror that was no doubt behind it would have been any better. I didn’t yet grasp and never fully understood, while she was alive, that we were moving into the final stages of that parent-child role reversal1, that this dynamic would only intensify, that my desire to protect her as though she were my child would become overwhelming and ultimately counterproductive.

The chemo area was chaotic the day we arrived, much busier than usual for reasons I can’t remember. We didn’t know the ropes yet—later, we’d find the bigger room with the televisions, where we’d watch large chunks of the World Cup that was unfolding in November and December instead of June and July because it was being held in Qatar, where it was too hot for summer sports. Later, my mom would bond with one of the nurses who also loved soccer and make a name for herself as the lady who went hilariously loopy after the Benadryl portion of her infusion (I’d extracted a promise from her not to rant about religion or politics, which she managed to keep for the first few weeks). But that first day we were in a crowded inner area with no windows nearby and no TV and we didn’t know anyone and everything was alien and frightening.

My mom looked around at the other people. Look how young they are, she murmured sorrowfully at the sight of the teens and twenty-somethings, and look how frail they are she would say of others, who shuffled in with walkers or in wheelchairs, scarcely mobile, neither of us able to imagine that would be her in a few months’ time. She turned on the charm—she always did—smiling and cracking jokes. I remember there was a shortage of chairs for visitors and I didn’t want to take one from people accompanying patients who seemed like they needed more support, so I left to get us coffee and snacks. But at some point after I came back, she said to me, “Look.”

She was watching a ladybug that had somehow found its way deep into that facility, probably attached to someone’s clothes or bag, and that was gamely hanging out on a nearby column, blissfully unaware that it had made its way into its own tomb.

She pointed that ladybug out to the nurses, to the patients on either side of her, to everybody. She was so worried about that ladybug and how it ended up there and what it was going to do and how it was going to get out of there. After four or five hours or maybe seventy because who knows when you’re in those types of places, wishing your life away indeed, it was finally time to go, and I scooped up the ladybug on her insistence because maybe she was gonna die (she was, at that stage, absolutely determined not to) but that ladybug was not gonna spend the rest of its days trapped in a chemotherapy room.

I probably had my mom on my arm as we walked outside and, I guess, the ladybug cupped in my hand, and I helped my mom into the car first—I really don’t remember. But what followed is so bright in my memory it might have been just yesterday: I had to walk a few feet to a shrub where the ladybug could presumably thrive and live out the rest of her halcyon days. I saw a man watching me from his car, clearly wondering what I was doing. I set the ladybug down on a bit of twig and she trundled about appreciatively. The man smiled then, and I smiled back at him.

So, that was my mom, in a nutshell. Whatever else was going on, she was hell-bent on saving that ladybug.

If my mom hadn’t been there—had she not been diagnosed with cancer— that ladybug never would have made it back outside. So I hope she was a young adult ladybug who survived the winter and had hundreds of babies in the spring. I hope those babies had thousands more babies and that in a thousand years her many descendants are still thriving, thanks to my mom.

Depending on her mood, my mom would have responded in one of two ways to this kind of musing.

She would have smiled and said something like, “That’s beautiful,” with tears glistening in her eyes, at peace with herself in a harmonious universe of wild living souls and unexpectedly numinous moments.

Or, she would have said:

“Damn! Who cares about the damn ladybug! I’d rather be alive! Can you believe she told this story like it was supposed to make me feel better? Damn!”

Anyway, every time I see a ladybug now, I think of you, Mom.

Reading

Writing the above made me think of the wonderful Graham Joyce novel The Year of the Ladybird, or as it’s known by its much less evocative US title, The Ghost in the Electric Blue Suit. This gorgeous coming-of-age tale is set in the sweltering English summer of 1976, which was accompanied by a plague of ladybirds (ladybugs), and tells the story of a sixteen-year-old boy who goes to work at a decaying holiday resort in hopes of somehow connecting with his long-dead father. It’s a subtle, evocative, the-ghost-is-barely-there-ghost-story by one of my favorite writers, who tragically died of cancer at the age of 59 in 2014, the year after this book came out. I read it before his death but devoured it as fast as I did every other novel by him because although I knew he had cancer, I couldn’t imagine that he was going to die. I’ve regretted tearing through it ever since—as though drawing it out, or not reading it at all, would have made a difference.

I was looking through old photos of my mom for one to illustrate this letter, and when I wasn’t really finding what I was looking for, I got out some recent ones—and I was shocked. Who was this old lady? There are only a handful, but in the ones from the final months I can see now that she was dying, when I couldn’t then; even in the earlier ones, though, taken years ago, I struggle to see the mother that I see my mind’s eye, who is perpetually never any older than her forties or fifties.

This one made me cry. I bet her reaction to the ladybug rumination would be along the lines of "Damn, I'd rather be alive..." but I wouldn't bet money I couldn't afford to lose.

Your mom sounds like she was loads of fun at her best and cantankerous at her worst. My mum was treated for lymphoma as her end approached, but she died at 94. Graham died way too young, and I had only discovered him about 5 years before. At least with authors, their words and thoughts live on. Happy Solstice 🌝🌻🏖️